For in breaking into my own body of speech, opening up the gaps and listening to the silences in my own inheritance, I perhaps learn to tread lightly along the limits of where I am speaking from. I begin to comprehend that where there are limits there also exist other voices, bodies, worlds on the other side, beyond my particular boundaries. For in the pursuit of my desires across such frontiers I am paradoxically forced to face my confines, together with that excess that seeks to sustain dialogues across them. Transported some way in to the border country, I look to a potentially further space: the possibility of another place, another world, another future.[i]

[i] Iain Chambers, “The impossible Homecoming,” in Migrancy, Culture, Identity, 1994 (Routledge, 1994, 5)

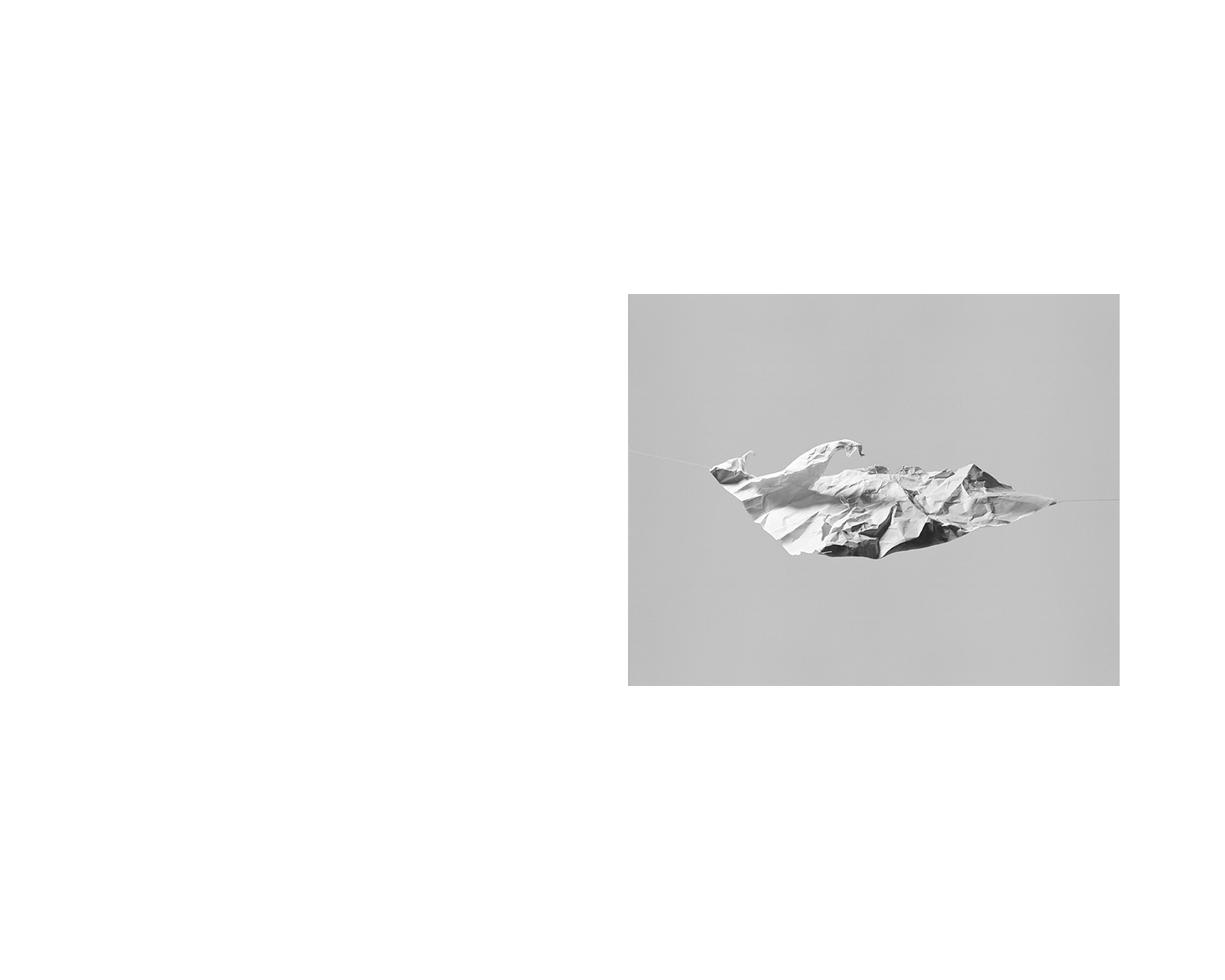

Mysterious Island derives its title from Jules Verne’s 1874 science fiction novel, in which a group of explorers aboard a hot air balloon crash-land on to the shores of a rocky, volcanic island. Upon calculating their location—an unfathomable distance from any familiar landmass, far outside the route usually followed by ships—they resolve to consider themselves “not as castaways, but colonists, who have come here to settle,” remarking that the island will one day appear “quite civilized.” Standing atop a central mountain range, in a position that permits a view of the island in its entirety, they begin by naming the island itself and all its geographic constituencies, asserting language as the first step in their colonizing mission. They continue vigorously to declare borders, classify and categorize fauna and flora, pioneer pathways, and conquer the terrain through a series of marvelous engineering feats. The goal: to chart the island until nothing remains unknown.

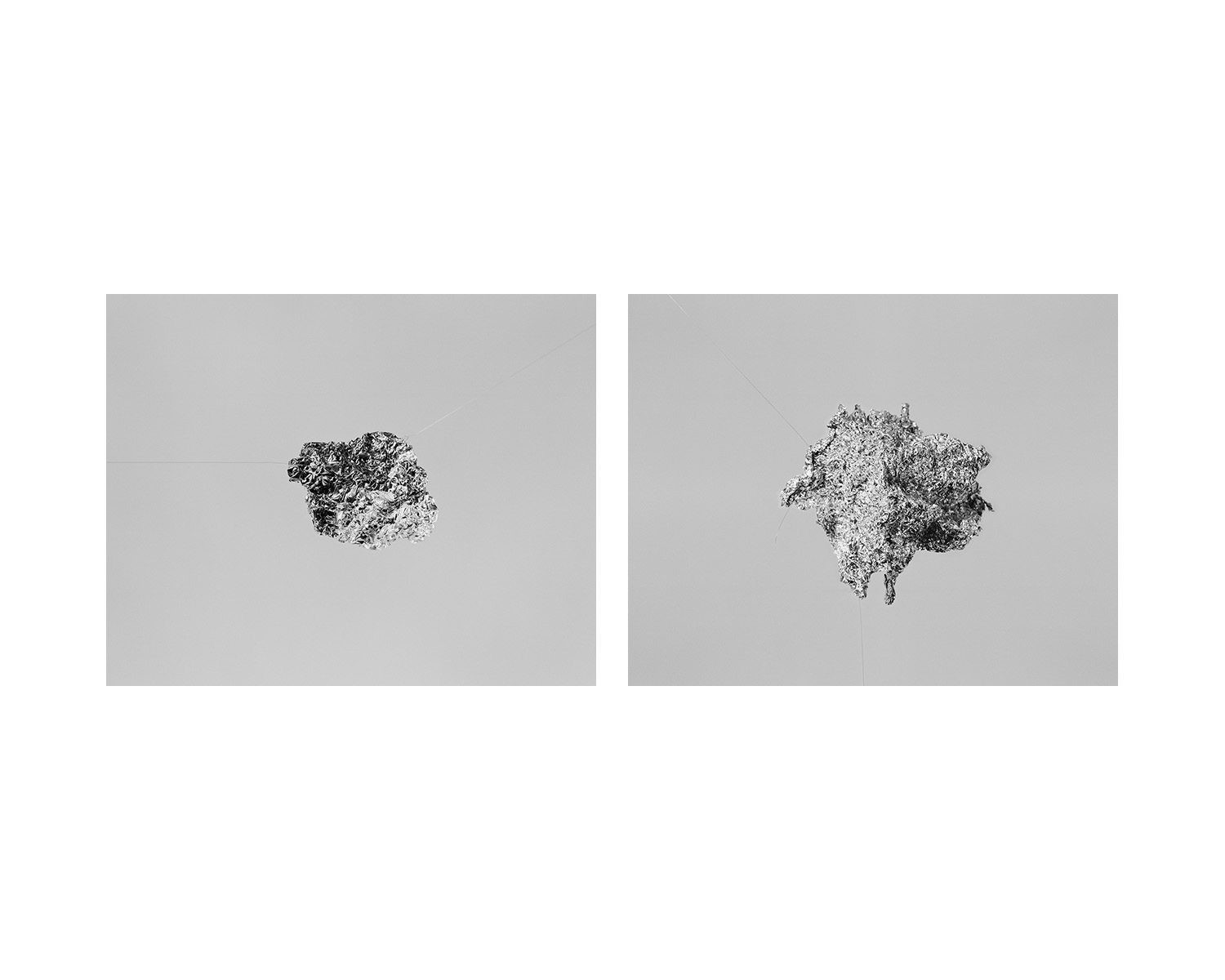

Mysterious Island examines this prevailing drive towards order, as observed in the naming and claiming of a fantasy space. Responding to transition, instability, and uncertainty, I explore fears of the unfamiliar and a subsequent desire to bring the world into control—manifest not only in the taming of geographical space, but also in the construction of language, meaning and identity. Here, a map becomes a metaphor for the way in which we identify and understand our selves: ‘I’ am a landscape that is separate from ‘you.’

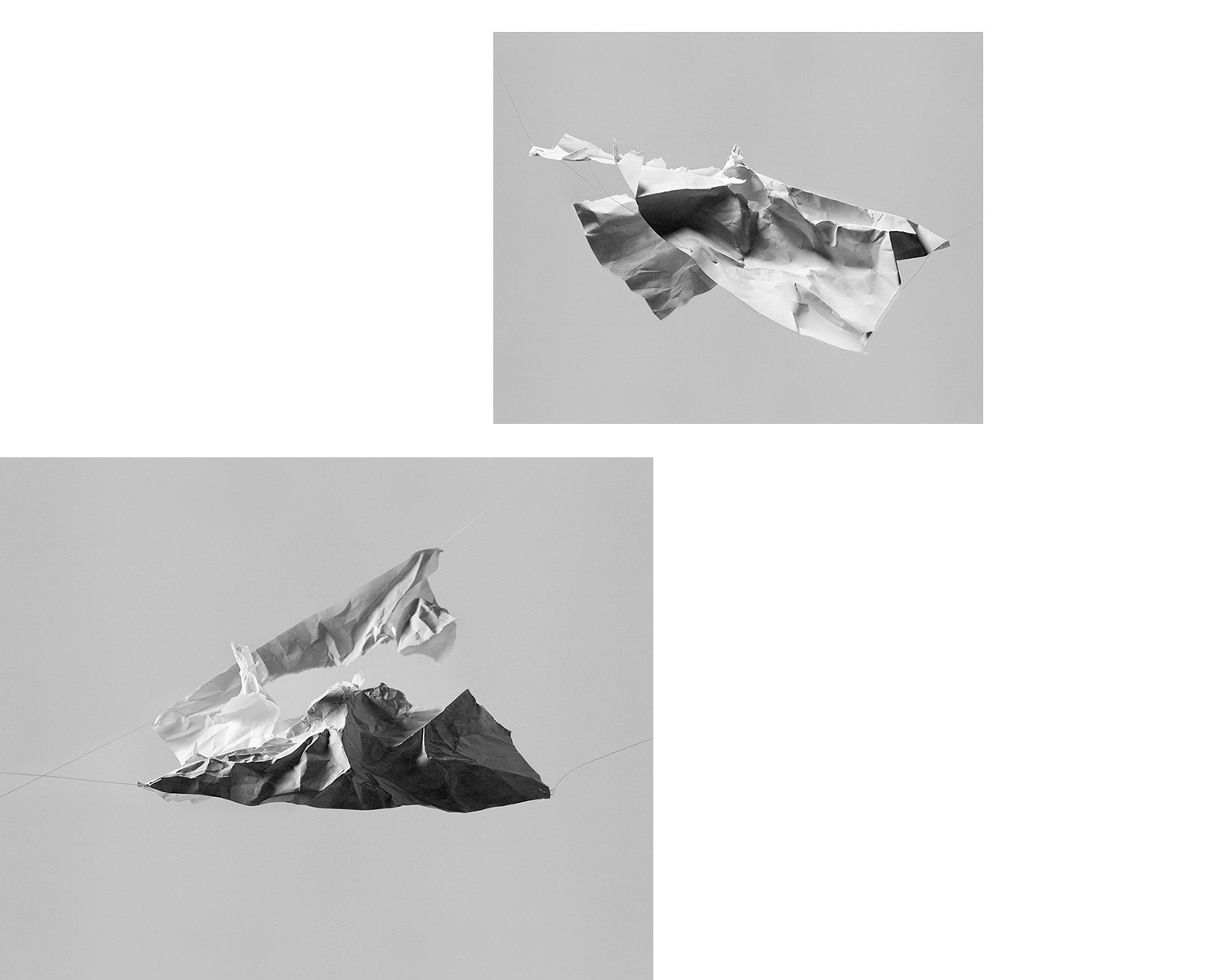

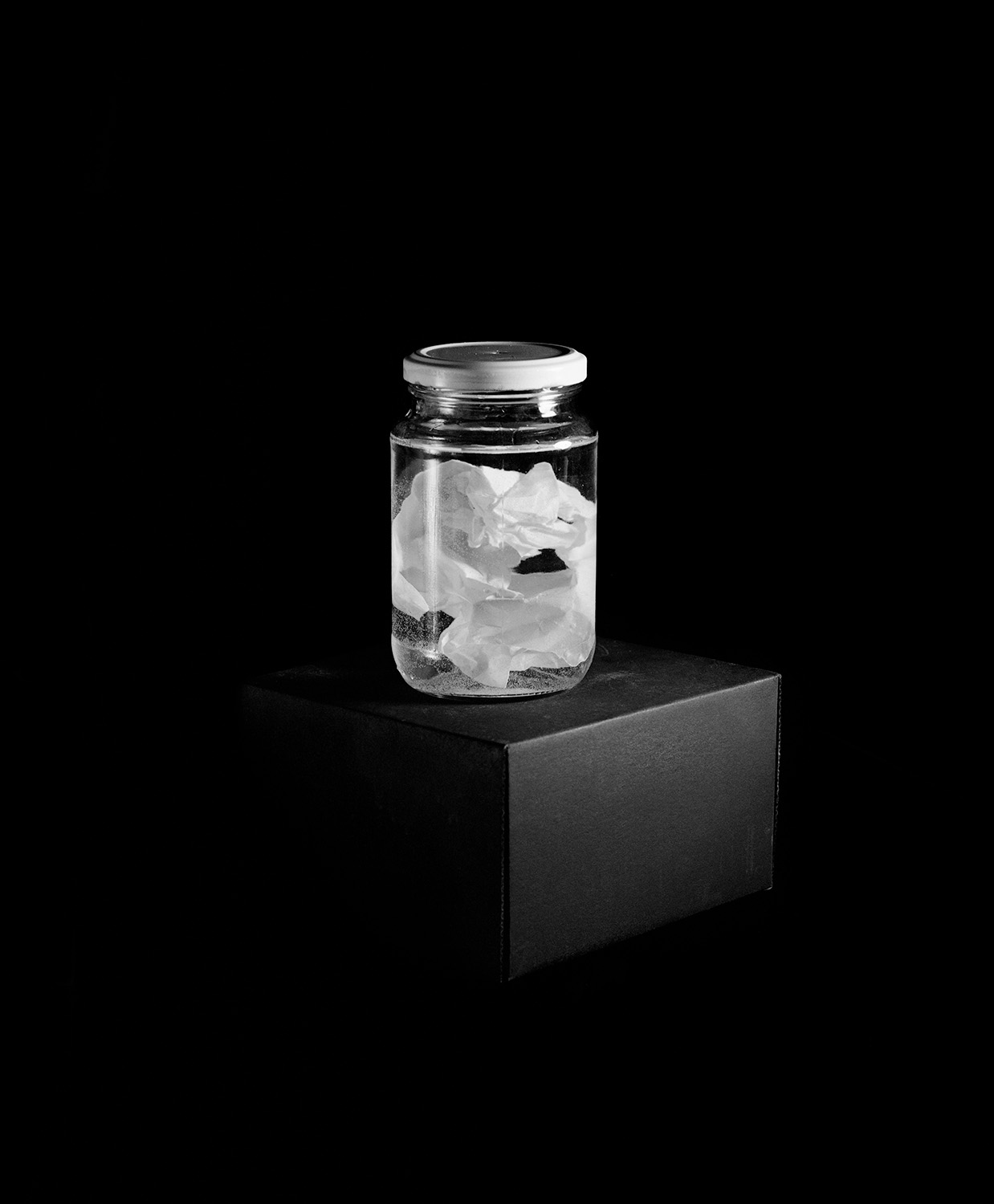

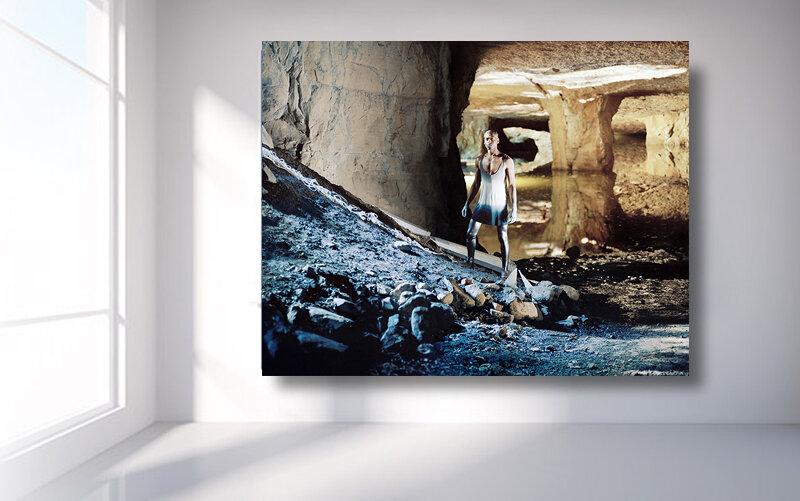

Through the staged photographic tableau of Mysterious Island, I act out my own impulse to construct meaning and impose order upon a landscape, using role-play as a way to pick these narrative structures apart. Confronting a deep-seated fear of the unknown ‘other’ that lies at the heart of our drive for control, I acknowledge that I too am a place, breaking open the borders and the limits of ‘where’ I am speaking from. Performance now becomes a ritual: a way to engage the body as a site of transition and fragmentation, in seeking more fluid ways of moving through the world.

Staged in both my home country, South Africa and adopted home, New York, the crumbling dystopian landscapes pictured show discernible signs of human intervention: a deserted mine collapsing into the Johannesburg horizon, a tunnel cylindrically ploughed through the Appalachian mountain side. The ‘field notes’ too becomes geographies, the trace of their observations erased into the crumpled, blank white of an empty page. Mysterious Island does not endeavor to construct a triumphant geography of conquered, charted space, but rather to invert that triumph, dismantling order to make way for something new. If there was a total annihilation of all familiar structures, what possibilities could arise from the rubble?